White-Nose Syndrome Training Module

- Introduction

- What is White-nose Syndrome?

- How does White-nose Syndrome impact bats?

- Where did WNS come from?

- How does WNS spread?

- Why is it important to prevent the spread of WNS?

- What are the best ways to decontaminate your clothing, gear, and boots?

- What other procedures do I need to follow to comply with approved protocols?

- Summary

Introduction

White-nose Syndrome (WNS) is a disease that is highly contagious to hibernating bats. Unfortunately, WNS has a very high mortality rate for a number of common bat species that dwell in caves in the United States. While the disease is primarily spread by bat-to-bat contact which then infects the caves they visit, it is possible for humans to transport the disease between caves. As such, all cave visitors must take practical precautions to assure they are not part of the problem in spreading WNS.

White-nose Syndrome (WNS) is a disease that is highly contagious to hibernating bats. Unfortunately, WNS has a very high mortality rate for a number of common bat species that dwell in caves in the United States. While the disease is primarily spread by bat-to-bat contact which then infects the caves they visit, it is possible for humans to transport the disease between caves. As such, all cave visitors must take practical precautions to assure they are not part of the problem in spreading WNS.

This training module will further explain what WNS is, how it is spread, and what can be done to prevent it from being transported by humans between caves used by bats.

What is White-nose Syndrome?

White-nose Syndrome (WNS) is a disease that can be fatal to hibernating bats. The disease received its name from observations of a white "powdery" substance on the muzzles of hibernating bats. Research has determined that the white substance is actually a newly-discovered fungus named Pseudogymoascus destructans. The fungus, thought to be an invasive from Europe, is interesting in that it is most viable at 40 to 60 °F and high relative humidity, both characteristics found in caves.

Fungi reproduce and spread by spores, nearly-microscopic "seeds" that are light enough to float in air, become attached to bats, cave surfaces, clothing, equipment, packs, and boots, and subsequently transported to other caves. The spores can remain viable outside a cave environment, so it is essential to properly clean and decontaminate caving apparel and gear between each cave trip, so that it is not spread by cave visitors.

The spores can be killed by various common household cleaners, or by exposure to hot water, as will be discussed later.

How does White-nose Syndrome impact bats?

Initial observations that raised concerns about WNS were that hibernating bats were becoming unusually active during winter. Bats use a hibernation strategy to survive during the winter months when no food (mainly flying insects) is available. If bats become active, they burn their fat reserves and die before spring. Early speculation was that the fungus was somehow disrupting the bat's ability to hibernate, possibly by irritating the bat because the pathogen is similar to the fungus that causes athlete's foot in humans.

Initial observations that raised concerns about WNS were that hibernating bats were becoming unusually active during winter. Bats use a hibernation strategy to survive during the winter months when no food (mainly flying insects) is available. If bats become active, they burn their fat reserves and die before spring. Early speculation was that the fungus was somehow disrupting the bat's ability to hibernate, possibly by irritating the bat because the pathogen is similar to the fungus that causes athlete's foot in humans.

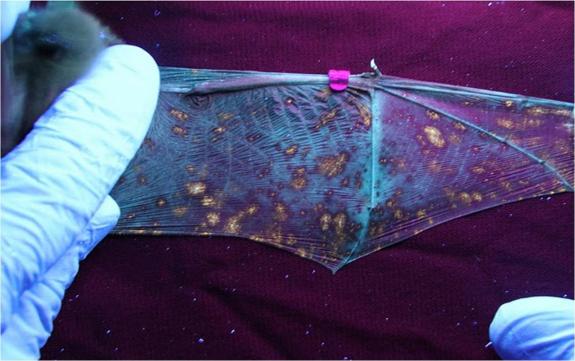

Subsequent research revealed that the fungus also caused lesions on the bat's wings. The wing membranes of bats are quite sophisticated in that they are important in many physiological processes such as regulating the animal's body temperature, water balance, and gas exchange with the outside environment. These life processes, vital to survival, are disrupted when healthy wing membranes are digested by the invading fungus.

Finally, it is suspected that when bats are in torpor (reduced body function when hibernating) that their immune systems are also reduced, thus decreasing their ability to resist the onset of WNS. Basically, the bats are defenseless in fighting the effects of the fungus when hibernating.

Research has shown if the bats can survive the winter, the damage to their wings can quickly heal; but it is unknown if these bats are more or less susceptible to the disease the following winter.

Where did WNS come from?

Current thoughts on the origins of the fungus point to caves in Europe. However, the bats that hibernate in these infected European caves do not seem to be impacted by the disease. This suggests that the bats there may have built up natural immunities to the disease, something that bats in North America presently lack.

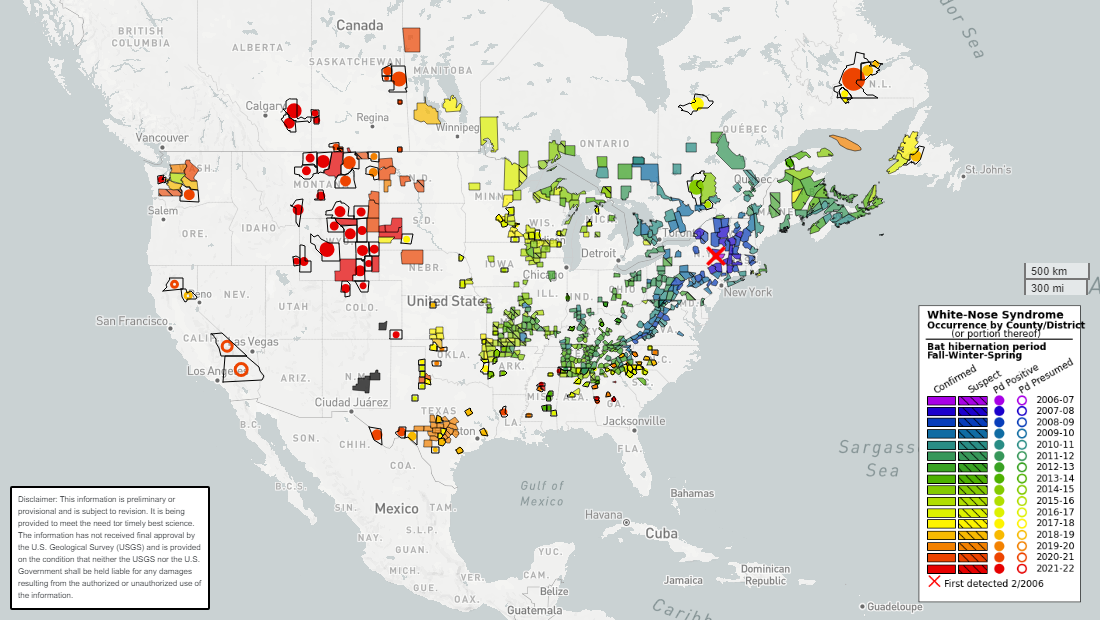

The first documented North American infestation of WNS occurred in Howes Cave in upstate New York in 2006. Exactly how the fungus crossed the Atlantic is currently unknown.

How does WNS spread?

The primary methods of the disease spreading are from bat-to-bat contact and bats exposed to infected caves. The social lives of bats are complex. Cave-dwelling species spend the "cold" months hibernating in caves, and the remainder of the year in wooded landscapes that are often hundreds of miles away from where they winter. Female bats often have maternity colonies which are opportunities for physical contact to transfer the fungal spores, which eventually get carried by the bats to new caves each winter. Male bats may form summer bachelor colonies in caves, again socializing with bats from different areas. The spread of WNS from its origin in New York has been very progressive and efficient, and has systematically expanded to most significant hibernacula in the eastern half of the United States and Canada, following predicted paths.

The primary methods of the disease spreading are from bat-to-bat contact and bats exposed to infected caves. The social lives of bats are complex. Cave-dwelling species spend the "cold" months hibernating in caves, and the remainder of the year in wooded landscapes that are often hundreds of miles away from where they winter. Female bats often have maternity colonies which are opportunities for physical contact to transfer the fungal spores, which eventually get carried by the bats to new caves each winter. Male bats may form summer bachelor colonies in caves, again socializing with bats from different areas. The spread of WNS from its origin in New York has been very progressive and efficient, and has systematically expanded to most significant hibernacula in the eastern half of the United States and Canada, following predicted paths.

The fungus spores can also be transported by human visitors from infected caves to other caves. While the likelihood of human-facilitated spread of WNS is thought to be small, the risk is significant because the distance could be considerably greater than the natural progression caused by the bats. Thus, it is very important to prevent human-caused "jumps" into uninfected regions.

Even within infected regions such as Indiana, precautions should be taken to not spread the spores into uninfected caves that currently do not harbor bats, as these could become safe havens for bats in the future.

Why is it important to prevent the spread of WNS?

The obvious answer is to keep cave-dwelling bats from going extinct. While there is little that cavers can do to prevent the natural spread of this disease, we must take the necessary precautions to assure the fungus and spores are not transported between caves by humans. The procedures take very little extra effort and should become routine practices for all cavers and other groups who visit caves.

What are the best ways to decontaminate your clothing, gear, and boots?

The US Fish & Wildlife Service has published several versions of their Decontamination Protocol. However, the following summary may prove easier to understand.

After each Indiana cave trip, properly decontaminate anything that went into the cave, or may have been in contact with anything that went into the cave. If you follow this rule, there is really nothing more you need to do prior to your next cave visit.

The post-trip decontamination process starts by rinsing off all visible mud from your clothing, equipment, and boots. Either hose things down in the driveway with a spray nozzle, or soak and rinse in a utility sink. Pay particular attention to removing the mud in the lugs of your boots.

After rinsing, for clothing, packs, porous equipment, soft vertical gear, ropes, and boots, the best approach is to soak everything in hot water (125 °F or greater - you might have to adjust your water heater slightly) for at least 20 minutes. Alternatively (except for vertical gear and ropes), you can soak items in a 1:10 dilution of bleach, a 1:128 dilution of Lysol IC Quaternary disinfectant, a 1:128 dilution of Professional Antibacterial All-purpose cleaner, or a dilution of Formula 409 Antibacterial All-Purpose cleaner for at least 10 minutes, then rinse thoroughly. If your clothes washer has a soak cycle, a hot temperature setting, and a "bleach" dispenser, you can completely automate the entire process for your clothing and other soft items.

For hard and non-porous equipment (helmet, lights, cameras), wipe down all surfaces with Lysol disinfectant wipes or spraying them with Lysol disinfectant spray. You should also spray the bottoms of your boots as an added precaution.

Finally, if you plan to visit any caves in uninfected regions such as the western half of the United States and Canada, never use clothing, equipment, or boots that have been used in Indiana caves, regardless of how well they may have been decontaminated.

What other procedures do I need to follow to comply with approved protocols?

The US Fish & Wildlife Service suggests taking precautions to avoid contaminating your vehicle interior and trunk areas, which could then indirectly contaminate clean caving clothes and gear on subsequent trips. The approach would be to never let "dirty" clothes or gear contact your vehicle by carefully bagging all post-trip clothing and gear away from your vehicle. Use large heavy-duty trash bags and seal the bags with duct tape or tie the bags before placing them in the vehicle. To make this procedure effective, each caver needs to "plan ahead" and place their clean change of clothes and shoes in the trash bag prior to entering the cave. The clean-clothes bag ideally would be stored away from the vehicle before the trip so it can be accessed without having to open your car upon returning. You would then change into your clean clothes and bag your dirty clothes and gear prior to opening your vehicle.

It is understood that it may be impractical to securely store your clean clothes away from your vehicle while you are in the cave, so at a minimum have your clean change of clothes pre-bagged and stored in the vehicle so you can retrieve the bag upon returning and change away from the vehicle.

It is also understood that in some situations, for privacy concerns, it may be impractical to completely change away from your vehicle, but at least remove the outer layers of caving attire away from your vehicle.

The main precaution is to do everything practical to prevent transferring the WNS fungus and spores into your vehicle that could subsequently re-contaminate future caving clothes and gear.

Summary

This training module has explained what White-nose Syndrome is, how it is detrimental to our cave-dwelling bats, how it is or can be spread, and what cave visitors can do to prevent being a transportation vector to uninfected caves and regions.

You may now download the WNS Training Acknowledgement Form to complete and forward to the Access Coordinator.